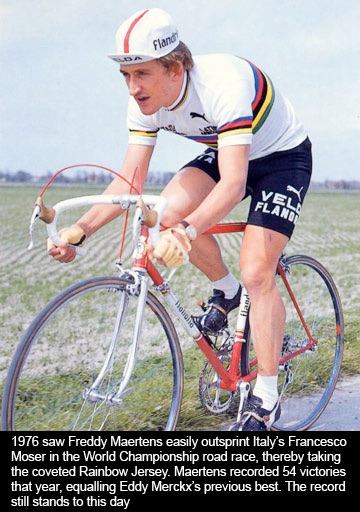

Freddy Maertens’ name is inseparable from the Flandria legend. Maertens stayed at Flandria for most of his career, during which time he became the greatest winning machine cycling has ever seen. He was at his peak in 1976 where he won Flandria’s second professional road race title, and he also took a record-equalling 8 stages of the Tour de France, which also gave him the Green points jersey. Maertens wore the leader’s Yellow jersey for half of the 1976 Tour. His tally of victories in 1976 was an astonishing 54, the most victories ever by a professional in a single season, tied with Eddy Merckx’s 1971 total.

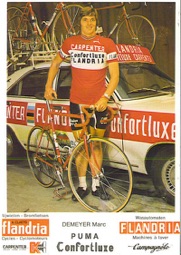

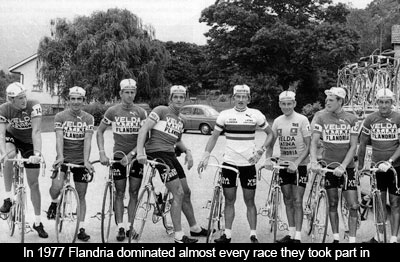

Pollentier also continued to develop, and when he, Maertens and Demeyer were at their best in 1977, winning became almost routine. Flandria bikes racked up their greatest haul of victories in a single season - 103. 1977 was notable for another reason. Flandria offered a pro contract to the young Irishman Sean Kelly, who began an apprenticeship under Freddy Maertens, which was effectively a kind of sprinting masterclass.

In the 1977 Tour of Spain the Flandria team obliterated the opposition. Maertens won the prologue and led from start to finish, winning an unprecedented 13 stages, the overall classification and the points jersey. 14 out of the 20 stages were won by Flandria, with Pollentier taking the other stage win.

As the red tidal wave swept into Italy for the Giro d’Italia, Flandria’s dominance continued. Once again Maertens won the prologue and took the leader’s pink jersey, which Flandria defended until stage 5 when it was taken by the Italian Francesco Moser. By the time the race sped into Mugello, Maertens had already won 7 stages, was expected to take win number 8 and regain the pink jersey in the following day’s time trial, where he was the favourite to win. The run-in began as usual, with Pollentier taking the lead and Demeyer right behind, ready to take Maertens into the final kilometre, where he would power past for the win. However, in the sprint, Maertens was elbowed and crashed horrifically. Unconscious and bleeding, he was rushed to hospital where his wounds were stitched and his broken wrist was put in a cast. The following morning he was in so much pain that he was unable to start the day’s stage. Such was the solidarity of the Flandria team that the whole squad voted to quit the race and go home to Belgium. Maertens managed to convince them, however, that they should continue in his absence. Now on a crusade, the team’s determination was even greater. Demeyer won two more stages and Pollentier outclimbed Moser in the Dolomites, taking back the leader’s jersey and holding on to it until the end of the race to claim the overall victory.

By now, Flandria had won every race on the calendar except for Milan-San Remo and the Tour de France, and in 1978 that elusive Tour win became their number-one focus. Maertens was not a good enough climber to be a yellow jersey candidate, so the team’s overall strategy depended on Pollentier performing well in the mountains. Pollentier had shown he was in-form having just won the Dauphiné Liberé. If Pollentier could take the yellow jersey in the Tour, Maertens the Green points jersey, and Demeyer stage victories, Flandria would make an indelible mark on the Tour’s history books.

Initially, the plan worked to perfection. Maertens won two early stages and had a firm grip on the green jersey, Pollentier had the climbers’ polka dot jersey, and even Sean Kelly had won a stage in what was his first Tour de France. On the crucial stage to Alpe d’Huez, Pollentier broke clear of the pack and soloed to victory on the murderous ascent, increasing his advantage over his rivals and claiming the yellow jersey. Flandria now owned all three principle jerseys in the Tour: yellow, green and polka dot, and it seemed that they would surely hold onto them until Paris, which was now only 6 days away.

What subsequently transpired, however, did not go according to plan. Pollentier, exhausted and suffering from extreme dehydration after the climb to Alpe d’Huez, was unable to provide a urine sample at the doping control. Failure to provide a sample is treated as equivalent to a positive drugs test and Pollentier was controversially excluded from the race. Maertens, however, retained his green points jersey all the way to the Champs Elyseés and Demeyer took a further stage victory, while the Portuguese rider Joaquim Agostinho ensured Flandria still made the podium in Paris, taking third overall.

Flandria’s final season in 1979 saw the team again miss out on overall victory in the Tour de France, with Joaquim Agostinho again taking third.