Motor-Paced landsvägslopp.

Tea-Time at the Parc

J. B. Wadley on Tom Simpson’s Sensational Bordeaux-Paris; Sporting Cyclist July 1963

IT was the last 10min of Bordeaux-Paris. In the Press cars we tore over the Pont de Sevres, along the Avenue de la Reine, swung round the last sharp bends to the forecourt of the Parc des Princes. We sprinted to the little gate on the right, past the riders cabins, down the ramp under the track and out into the centre of the Parc des Princes, cool, green grass surrounded by 454m of pinkish track, and covered stands. Some 30.000 people were in the stands, but the ribbon of cement was empty, reserved for the winner of the 62nd Derby of the Road.

We knew who he should be, must be - but by some terrible mishap. still might not be. We had last seen him five miles from the finish, well away from his nearest rivals, going like mad and a certain winner barring accidents. For my part I refused to believe it all until I had seen him safely over the finishing line.

There was not long to wait. The commotion outside grew to a roar, the traditional gun shots were fired, a kind of conductor's cue to the trackside crowd to take over the chant of victory to Tom Simpson, first British winner of Bordeaux-Paris since 1896.

Tom was so far ahead of his rivals that he could have taken 5min over that last lap and still won. But unknown to us at the time, he had other plans. Almost for the first time for 200 miles he had spoken to his pacemaker, Fernand Wambst. about 2km from the Parc des Princes:

"We'll sprint for the prime!"

The prime was for 100,000 francs, £80 or so, a nice little sum, but really "peanuts" compared with the £1,000 first prize, big bonuses from his many sponsors, and the string of track contracts awaiting his signature.

It was a tremendous thrill seeing Tom sprint that last lap, for it proved that he had really won the Derby at a canter. Some may argue that the race was not all that important without Anquetil, Van Looy, Altig and Stablinski - and indeed, that argument has had its points for many years now.

But that last lap of the Parc des Princes, and that last hour on the road from the Dourdan hill %%here he soared away from his rivals, proved that Tom Simpson would have won the 62nd Bordeaux-Paris no matter who had been there. And so - the old-timers told me afterwards - could a man of Tom's class have won many, many of the 61 that have gone before. . . .

WAS the importance of Bordeaux-Paris on the wane? I wondered this for only a minute or two after my arrival in the capital of the wine country. I walked along the broad, sunny Allees de Tourny to the crossroads of the Cours de Verdun, where on the corner I spotted the Cafe de France, operations centre for the 62nd Derby of the Road.

Apart from two or three banners. there were no signs of unusual activity. True, it was not yet two o'clock on the Saturday afternoon. and official activities did not begin until four. But I remembered my last Bordeaux-Paris. in 1956, when the headquarters was in a sizeable indoor sports arena, the outside of which was well plastered with banners of all the firms connected in any way with the promotion, headed, of course, by "L'Equipe", the organising newspaper.

But today, H.Q. was Just a typical cafe with its terrasse. In the sun with a drink I asked the waiter if there was some big courtyard at the back of the cafd where the Bordeaux-Paris "control" would take place.

"No sir. It is here in the very place where you are sitting."

Then I realised the reason for the modest nature of the 1963 headquarters. On that 1956 "Derby of the Road," the race was Derny-paced throughout its 350 or so miles; this time the pace-makers did not come on to the scene until 150 miles had been covered. The most important H.Q. of the race was, therefore, not at Bordeaux itself, but at the takeover town of Chatellerault. At Bordeaux the officials would be concerned merely with the checking of the bicycles on %Nhich the 15 competitors started, a comparatively simple task; at Chatellerault their colleagues had the more complicated Derny machines to deal with, and their experienced and (often) astute drivers.

At this point another difference between the 1956 Bordeaux-Paris and the 1963 version occurred to me, and that was in the paced-all-the-way race we were able to get in an hour or two in bed before the 4.30 a.m. start: the 1963 partial-paced was scheduled to start at 2 a.m. . . .

I left the cafe to carry on its normal business for a while, but when I came back at four o'clock, just as the garcon had said. my little corner had been taken over by the officials, who were getting out their papers and settling down at tables. The place now looked more like a "control" with additional publicity banners hanging, and small barriers to fence off the area. They were hardly needed for the two-hour session, for the formalities concerned not the men of Bordeaux-Paris, but their bicycles. True, Peter Post and Van Est looked in for ten minutes, but this was only because they wanted to go for a short ride and had their bikes checked on the way. The other riders were resting in their hotels.

The technical formalities at Bordeaux were simple. The machines had to be those of "type in current use". The only measurement taken was that between the bottom bracket and the front spindle, which had to be at least 58cm. The idea, of course, is to prevent riders getting up too close to their pace. A big rider's machine - such as Post's - was easily within the limits, while little Le Menn's only just made it. Apart from the big chainwheels - 56 was the most popular "saucer" in use - the machines were normal enough, the only obvious difference between them being in colour. Violet. Mercier's; bronze, :Mann's; red. Sauvage-Lejeune's; blue, Gitane's; black Bertin's; and the cream, Peugeot's liberally decorated with black squares, domino fashion.

Apart from the 58cm test, the only further treatment the bicycles received was to have an official seal fixed around the seat cluster, and another on the front forks. Thus it would be easy for a commissaire to spot if a rider was using a machine that bad not been checked.

From M. Gaston Plaud, directeur sportif of the Peugeot team. I learned that his four riders would be having their big pre-race meal at 11.30 p.m. I was there an hour earlier. Down in the kitchen of the hotel, M. Plaud's team of helpers had more or less taken over, and were busy filling bidons and preparing rations for riders, pace-makers and helpers for the long day in the saddle. It was all reminiscent of preparation for a "24" or an "End-to-End."

I sat in the lounge of this first-class hotel watching helpers carrying the vast stock of provisions, spare wheels, tyres and clothing to the vans outside. A mechanic sat with me for a few minutes. "What has happened to Brian Robinson?" he asked. "We had his Peugeot bikes all ready for him for the road season, and they were hanging up in the service des courses. In the end, Hoevenaers took them over. A pity Brian has retired. A good rider and a nice fellow."

Then one of the trainers joined us. I had the temerity to remark that the unpaced part of Bordeaux-Paris, the first 250km to Chatellerault, seemed a mere formality. The race never really started until the Dernys took over.

"Bordeaux-Chatellerault nothing?" the newcomer said. "I think it is something very important indeed. They may all arrive at Chatellerault together, but they will not all arrive in the same condition. Those who have been the best looked after, and who have best looked after themselves for eight hours or more, will be the best equipped for the final battle behind the pace-makers.

"You might as well say," continued my critic severely, "that because a sprint race is won in the last 200 metres. the first 800 metres at a slow pace do not matter. They do - and so do the 250km from here to Chatellerault."

At 11.20 p.m., down the stairs came track-suited Tom Simpson. The theory was, he told me, that he should sleep all day. In fact he hadn't slept at all. Now he had to cat, and wasn't so sure that he could. Earlier on he had eaten a mixture in which honey was largely involved, and he believed that had caused the sweating and spell of dizziness.

“The last time I felt like that was just before the world road championship in 1960," he said. "I turned out to be in top form really that day, so perhaps this is no cause for alarm. Nerves, maybe."

I went with him to the restaurant and sat at a neighbouring table while he and his team-mates Forestier, Rentmeester and Hoevenaers bad their meal, the disposal of which caused Tom no bother after all. Menu: vegetable soup; raw grated carrots; a big underdone steak with boiled rice; two yoghurts. (The others took sugar with theirs, Tom did not.) No wine, but mineral water (Badoit) into which Tom squeezed the juice from slices of fresh lemons. The meal lasted 45min or so, during which time I don't think bikes were mentioned once, and Bordeaux-Paris not at all. Cars and their performances were the favourite topics.

Then, up in his hotel room, Tom in no way acted like the man about to start the most important race of his career. He went leisurely about packing his valise with things not wanted on the 350-mile voyage ahead, and looked over his spare clothing for the race. A short length of zip half-way up the side of his new long-sleeved Peugeot jerseys puzzled him (later he told me it was an idea of Gaston Plaud's for pulling them off easily).

He blacked his shoes carefully, finding as he did so that the laces wanted changing. He rummaged in a musette. "Good girl," he muttered as he found a new pair. Helen, his wife, although with important and happy events of her own to think about, had remembered to keep that musette stocked with the small but important items of her husband's trade. Tom talked of Helen, and the other two Simpson girls: Jane, 14 months, and Joanne, five days; how one day they might settle in Australia. "I may go to Australia next winter to race," Tom said. "A couple of open-air six-day races with John Tresidder, and the Sun Tour."

What if he won Bordeaux-Paris. Would he ride the Tour de France?

"Almost certainly not," he replied. "I would concentrate on the world road championships, pursuit and road. Anything happening at home this week-end?"

I told him that London-Holyhead (that British Bordeaux-Paris) had finished a few hours ago, that the, 25 miles championship would begin in an hour or two.

Then leaving Tom to complete his preparations I went off to the headquarters zone which now, at 1.30 a.m., was alive with activity. Le Menn was the first rider to arrive. wearing the lightly tinted glasses favoured by most of the field, except the two Merciers, who sported the goggles in vogue in the days of their directeur sportif, Antonin Magne. A big cheer greeted the arrival of Tom in his tammy, plentiful jerseys and heavy leg warmers. After signing on, Tom withdrew from the crowd: somebody brought a chair front the cafe and on it he relaxed for the last five minutes before the call to the line.

Then the whistle, the line-up of the 15 riders, the neutralised depart for 2km along the quays during which Peter Post does a mock pace-following act behind a gendarme's motor bike, over the Garonne by the St. Pierre Bridge behind the car of assistant race director Albert De Wetter, who drops his flag at 1.58 a.m.- and the 62nd Bordeaux-Paris has begun.

There is a long hill out of Bordeaux. with a cycle path alongside. As the little peloioll of competitors pedals easily up the slope, a score of moped riders buzz up on their right to enjoy a 5min close-up of the jockeys of this Derby of the Road. There are big crowds out to cheer them until the big cross-roads at Les Quaire Pavillions (until two years ago always the starting point of Bordeaux-Paris) - and then out into the open country. Not that the road is deserted. Plenty of people (many in dressing-gowns) still up to see 15 riders take no more than 15sec to go by. . . . The roads are not closed. The pocket-peloton keeps well to the right, and now and then the motor cycle police pilot ordinary road users by, but their colleagues ahead have brought the oncoming traffic to a halt, which is just as well since most of it comprises huge lorries and trailers.

The 15 bowl along at evens, a motley crowd in their woolly bonnets and over-clothing, chrome-plated fittings flashing in the car lights, sturdy legs economically, turning gears in the mid-70s. Now and then the Belgian and French TV cars go alongside, a technician in the rear scat holding out high-powered lamps. The effect is quite fascinating. Shadows of riders and machines are thrown sharply on to the adjacent vineyards which, themselves flooded with this artificial light, look like a great, green sea as wave after wave of vines ripple by.

Dawn. mist, birdsong in the hedgerows, chatter among some of the 15. At 5.20 up comes the sun slightly to our right, a great red plateful of it rising over the town of Angouleme, where the first feeding is allowed direct from the team cars.

Assistant race director De Wetter is in car No. 2. 1 am in car No. 3 with his co-assistant. Nicely placed. too, right behind the riders. able to judge their various styles from close quarters. Tom is pedalling comfortably. I reflect that in the days of G. P. Mills, who won the first Bordeaux-Paris in 1891 and in 1896 when Welshman Arthur Linton dead-heated with Gaston Riviere, the dropping of the ankle at the top of the pedal stroke was the style of the champions. Here, now, are 15 stars all with ankles raised around the entire orbit. An Englishman. three Belgians. five Dutchmen and six Frenchmen can't be wrong. .'

From time to time riders in ones and twos have stopped by the road-side "for little personal needs" as French Pressmen so nicely put it. About half-past seven Tom stops, and as he comes back alongside I can see he is in good shape.

"Nearly went to sleep three times in the first hour or two." he says. "I shall be glad when the race really starts."

Before going right back into the bunch Tom rides hands off, doffs his top jersey, slings it round his neck with the sleeves tied umpire fashion where it remains until his team car comes up to collect. In another 50km or so, just south of Poitiers, practically the entire field hurriedly dismounts in front of their parked team-vans for the traditional "striptease" and hurried rub down. We are now approaching the take-over town of Chatellerault.

Until now there have been few Press cars behind us. Now they are beginning to build up, because whatever my trainer friend thinks of the unpaced part from Bordeaux to Chatellerault, my colleagues do not think it worth while following it. In a way they are right, for while it is heroic to stay up all night watching the whole affair, the man who has had a good night's sleep will write a better story immediately after the race than his drowsy colleague.

On the outskirts of Chatellerault now. From a bunch of 15, the riders become a string, gradually warming up the pace and almost sprinting the final unpaced miles through the twisting town. Underneath the big overhead banner in the Boulevard Blossac are the 15 Dernys, which accelerate as the riders aproach and contact is made. Through the puffs of smoke from the buzzing machines I spot riders and their pace-makers shaking hands before getting down to business. Behind us are 15 reserve pace-makers ready to take over.

At this moment there are 299 kilometres of paced riding ahead to the Parc des Princes, and almost immediately the red flag goes up in car No. 1, signifying that a break is in progress. Incidentally, M. Jacques Goddet is wielding that flag; as it is the first time we have seen him, it may prove, after all, that Bordeaux-Paris really does begin at Chatellerault!

It is easy to find who is in the break by establishing who is not in it.... Six riders are not: Post, Van Est, De Roo, Lefebvre, Hoevenaers and (I am glad to see) Simpson. News soon comes that Jean Forestier has "gone" from the start, and the other eight (Delon, Maliepard, Nijs, Melckenbeck, Delberghe, Le Menn, Beuffeuil and Rentmeester) are grouped a minute or so behind. As the Simpson group is only riding at 40km.p.h. it is not surprising to hear that Forestier is running away at the front and at Saint Maure (264km to go) he has a lead of 6min. This. of course, is no cause for alarm to Simpson. since Forestier is his team-mate. Moreover, Tom is riding with the two race favourites, De Roo and Post, and will be ready to follow any moves they make to reduce the margin.

It is not quite so hot as we expected, the wind slightly from the north. Forestier battles on, but finally is caught after a 142km break and dropped by Maliepard and Rentmeester. the latter, again, being a team-mate of Tom's. When the lead gets to nine minutes, and there is still no serious reaction from Post and De Roo. I begin to get uneasy. Has pace-maker Fernard Wambst, in his anxiety to curb the impetuosity of follower Simpson, become too cautious? It seems that if Tom wants to get up there to the front he will have to go on his own, since neither Post nor De Roo seems inclined or able. As for that other great Dutchman, Wim Van Est, whose great calf muscles are almost touching his down-tube bidon, he is suffering and will be dropped soon.

Then Simpson attacks, or rather Wambst steps up the pace. It is the first move of a two-pronged effort destined to make cycling history.

Without fuss or bother, the Anglo-French "tandem" moves up relentlessly at 35 m.p.h. towards the front, dropping the failing Forestier and the other "intermediaries" on the way. As .he spires of Chartres Cathedral come into view so does Tom see ahead on the road his two objectives: Rentmeester and Maliepard.

Beyond the cathedral city Delberghe comes back from behind, and at Ablis we are astonished to see little Le Mean fight his way back, too. Five men in the front, then, with 64km to go!

I have now changed cars. The assistant director in my first has necessarily to keep behind with the stragglers. I have come to see an Englishman win Bordeaux-Paris, and I mean to do so. Finding another seat is dead easy. Everybody wants to get a story from the only English journalist in the race! My new car has a distinguished "captain"; Pierre Chany, of "I'Equipe" (the man who last year described me as J. B. Wadley of the English magazine "Cycling!"

"Who, do you fancy, Pierre?" I ask.

"Delberghe or Simpson. If Simpson goes too early, the more regular Delberghe might fight back. Dourdan holds the key to the situation”.

Dourdan, chief obstacle of the Valley of the Chartreuse we are now approaching. Dourdan of the narrow streets and cobbled base to the hill that has played a vital part so many times in Bordeaux-Paris....

Beyond the other cars we can see the group of five. Pierre turns on the car radio and we hear the commentator from the front giving the greatest sporting news I have ever heard over the air. "Simpson attacks on the lower slopes of Dourdan .. . Delberghe resists for a short time. then is dropped by his Derny . .

Simpson pedals easily on, while the other four are stretched out behind ... Simpson 100 metres in the lead . . . well away . . . 200m at the summit...."

This is the critical moment of the whole race. Will Chany's prediction come true? Will Delberghe fight to regain his lost ground and knock out Tom in The last round of this 15-hour International contest?

It is the Valley of the Chevreuse of the great days. The woods packed with spectators, picnic tables abandoned. They've cheered Gauthier four times, Van Est three times, Bobet once to victory. Now they really roar this English Tommy on.

The radio again. ". . . Here now at Limours at the top of the hill, with 36km to go, Tom Simpson has a two-minute lead. He is riding so strongly that, bearing accidents, he must win Bordeaux-Paris. Behind the riders are beaten. . . ."

Despite the narrow roads, Press colleagues are drawing up alongside with the thumbs-up sign. "Tom is the first man!" sings out Jos Van Landeghem. "Bravo Tom - il est formidable" from Louison Bobetwith Jean in the Radio Luxembourg car. From M. Jacques Goddet is an undisguised expression of delight, and Rene de Latour and Roger Bastide are giving the boxer's victory sign.

But hold it.... This race isn't over yet. Hasn't Rene himself told us in these pages of mighty Bordeaux-Paris collapses of the past, of men riding like trains one minute and dead to the world the next? There's 20 miles to go, ups and downs, through towns, round nasty corners, dogs might rush out, a front tyre burst. Tom has nearly won three classics this year, and there is always the danger that he may still only nearly win this. Tom knows it, too, and so does Wambst. They take the corners cautiously (we have now passed the four others, who seem resigned to fighting for second place) and at last are safely in Versailles where thousands line the roadside.

"We must pass now and get to the finish," says Chant'.

On the famous Cote de Picardie, out of Versailles, we pass our hero, mouth open wide, head and shoulders heaving a bit, but his coup de pedale as steady as ever. The crowds are clapping, cheering and shouting Seem-son. Down to the Seine, over the Pont de Sevres, along the Avenue de la Reine, park the car, under the track up to the crowded Pare des Princes. No time even to get the cameras out of the bag when there is a series of gun shots from the tunnel entrance, the signal that a rider is about to enter.

In he comes, behind Wambst, reserve pace-maker trailing. Tom sprints that last lap to tremendous applause, throws high his hands in the air as he crosses the line as great a Bordeaux-Paris winner as there's been since G. P. Mills won the first in 1891.

Later, at the Peugeot celebration supper, Tom had little appetite and drank carrot juice. Who had helped him most to win Bordeaux-Paris? I asked. "Two men: my Belgian trainer Gus Naessens, and my pacemaker Fernand Wambst," he replied.

Wambst was sitting a few places away, and he told me that their understanding was so great that they hardly spoke a word until 2km from the Parc when Tom called out, "On sprint pour le tour." (We'll sprint for the lap) Earlier, Jean Bobet had told me that Wambst had been carefully selected as Tom's pacemaker. Wambst had paced Kubler to victory in 1953, curbing the Swiss star's tendency to "battle" too much. Simpson is of a similar temperament, and "class," too.

The party did not last very long. Everybody was tired. But I and three Belgian journalists remained at the table. The champagne bottles were there, too. We emptied them promptly. Then Mr. Jerome Stevens of Het Volk ordered another.

"Tom comes from your country. He lives in my town, Ghent. Let us drink to your great compatriot, who I am proud to have as a neighbour," he said."

Bordeaux–Paris

DESPITE Harris, Patterson and Bunker, the biggest hero of all at the Parc des Princes on Sunday was Ferdi Kubler, who, in the course of the afternoon, roared on to the track behind a "Derny" and beat Van Est by five seconds to win the 365-mile Bordeaux-Paris — the Derby of the Road.

Although Van Est narrowly failed to bring off his third win in the classic event, Kubler's biggest victory was not over the Dutchman, but over Francis Pelissier. Pelissier, who won the race in 1922 and 1924, is now directeur sportif of La Perle Cycles, who had engaged Kubler to ride under their colours in the Derby. Pelissier, however, was not satisfied with the thoroughness of Kubler's preparation, and when the Swiss rider found it impossible to be released from a track engagement at Zurich on the Thursday night, Pelissier announced La Perle would have nothing more to do with Kubler, and withdrew their support.

Furious, Kubler hurriedly arranged for his Swiss marque Tebag to sponsor him. "If ever I have a bad time during the race, just say 'Pelissier' to me, and I'll soon recover," said Kubler to his chief pace-maker Ferdinand Wambst.

The race started at 1.30 a.m., and the eight competitors rode unpaced for the first 253 kms. to Chatellerault, where the Derny pacemakers took over. The last 125 kms. saw a furious battle between Van Est and Kubler, and when the Swiss failed to get away, pacemaker Wambst advised Kubler to reserve his effort for the final sprint. This he did, and beat Van Est (and Pelissier) at the Parc des Princes. Average speed for the whole race was 24 m.p.h., and for the final 319 kms. behind pace, 27 m.p.h.

The field of eight was the smallest in the 53 years the race has been run. The “Derby" has always been run in May or June until this year, when the organisers changed the date until September in an attempt to relieve the overcrowded calendar.

Result 1953 - 52nd Bordeaux-Paris

1. Kubler 14h. 56m. 35s

2, Van Est at 5 seconds

3, De Santi at 5m. 3s

4, Ockers at 6m. 11s

5, Cieliczka at 8m. 50s

6, Diot at 12m. 18s

7, Stablinsky at 22m. 43s

Mahe retired.

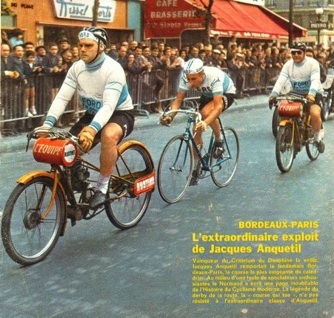

Den sista riktigt stora utmaningen

Bordeaux - Paris föddes i maj 1891 under en tid när allting

verkade handla om tävlingscykling. Nu ihågkommen bara

av gamla veterancyklister, och även de har bara gulnade

minnen av mästare omgivna av en svärm av hjälpryttare,

sökandes lä bakom en motoriserad cykel kallad derny eller

burdin.

Hjälpryttaren (The pacemaker) på sin motoriserade cykel

var en Sancho Panza stor och väldig för att ge så mycket

lä som möjligt. Hans följare (Stayer) en slank Don Quixote

på sin häst av metall.

Ett riktigt spektakel, en tävling som exprimenterade med

olika regelverk och inte mindre än 10 olika målstäder under

de sista 20 åren. En tävling som också dödförklarades ett

antal gånger men som märkligt nog återuppstod igen.

Många har i dag glömda storheter, som Henrie Pellisier, Gaston Rivierre, Georges Ronnse, Wim van Est, Bernard Gauthier och Herman Van Springel vilka alla var vinnare av denna märkliga tävling.

Den något mindre kända cyklisten Maurice Le Guilloux som slutade 2:a och 3:a under 80-talet beskrev tävlingen så här:

Det finns ingen strategi i Bordeaux – Paris ingen tacktik, det är bara var och en för sig.

Den är inte bara lång och hård utan också fruktansvärt snabb. Han fortsätter; bakom dernyn kan du nå 65-70 km/t och det stannar aldrig av, du bara koncentrerar dig och trampar. Fötterna börjar värka fruktansvärt och det är omöjligt att slappna av. Du kan inte se dig om kring och inte ens hämta andan under några meter. Vinden skiftar hela tiden och du knuffas hit och dit. Så är det trafiken, bilarna och långtradarna – det är otroligt farligt. Eter ett tag slår tröttheten till och du kan knappt ens få i dig något att äta. Jag skall tala om att de är så besvärligt att allt du vill är att vinna.

Så varför gör man det då frågar sig Le Guilloux. ”För äran. Detta är den sista riktigt stora utmaningen, en legendarisk tävling och en chans för mig att få vara en del av legenden”.

Men nu är den över, Bordeax – Paris gick i graven 1988 efter sin 85:e upplaga.

Tävlingen fick flera smeknamn, The Deyonne (Dean), The Derby of the road och Cykelmaraton. Journalisten och tävlingsarrangören Jacques Goddet gav det till och med namnet ”mästerstycket” efter Wallter Godefroots seger 1976, då tävlingen åter höll på att få en nyrenässans.

Men förs och främst var tävlingen framför allt en riktig ”tuffa pojkars tävling”

På slutet av 1880 tal hade cykeln nyligen sett dagen ljus,

och framför allt tre Franska städer hade tagit ”den lilla

drottningen” (som cykeln kallades i Frankrike) till sitt

hjärta. Dessa var, förutom Paris: Angers, Bordeaux och

Grenoble. Klubbar, banor och tävlingar frodades här,

särskilt längs stranden på floden Gironde i Bordeaux.

En tävling för trehjuliga cyklar startades så tidigt som

1889 och gick mellan Bordeaux och Paris (Georges

Thomas, Oscar Milotte och Maurice Martin behövde fem

dagar på sig för att tillryggalägga de 715 km).

Detta fick den lokala cykelklubben och tidningen cykelsport

att tända på idén om en tävling mellan Bordeaux och Paris

eller Bordeaux och Toulouse. Det viktiga var att den var

spektakulär för att fånga folks intresse.

Beslutet togs den 13 januari 1891. Det skulle bli

Bordeaux – Paris.

Eftersom Engelsmännen redan var vana vid sådana här övningar

kom de med ett fem man stark lag, beredda att ge sig ut i natten

för det 572 km långa äventyret.

Den 23 maj kl 05.00 på morgonen gick starten, hela vägen bakom pacers på cyklar. Vid kontrollen i Angouleme efter 131 km kom som förste cyklist engelsmannen Georges Pilkington Mills som redan skaffat sig ett gått försprång.

Vid nästa kontroll i Poitiers efter 245 km dit han anlände kl 15.45 hade han skaffat sig en ledning på hela 35 minuter vilket gav honom tid att inmundiga en rejäl stek och lite jordgubbar. Mills anlände till Tours (km 347) om kring kl 20.00 med över en timmes ledning till sin närmaste konkurrent.

I Paris väntade över 5000 åskådare på honom när han anlände kl 07.30 påföljande morgon. Han hade då tillryggalagt sträckan på 26 timmar 34 minuter och 57 sekunder med en snittfart på 21,5 km/t . Två kom Monty Holbein 75 min senare. 18 cyklister fullföljde allt som allt under de närmaste 4 dagarna inklusive fader Rousset, en 55 årig katolsk präst som gick i mål 14 timmar och 36 minuter bakom Mills och hade då även hunnit med att stanna för en fiskepaus!

Bordeaux – Paris tilltalade många olika typer av cyklister.

Den långa distansen uteslöt inte ens den tidens så populära

bancyklister efter som pacers spelade en så viktig roll. 30%

av en cyklists framgång kunde tillskrivas dem, om man får tro

två av den tidens verkliga specialister, Gauthier och Van Springel.

1899 startade Constant Huret en bancyklist som var specialist

på 24-timmars lopp bakom pacers. Han drog fördel av att pacea

bakom en bil för att vinna i sitt första försök, trots fem rejäla vurpor

som förorsakades av usel bilkörning.

Huret behövde 16 timmar och 35 minuter för att komma i mål och

cyklade med en snitt hastighet av 35 km/t, ett rekord som stod sig i

34 år.

Om pacers var loppets charm var det också dess förbannelse. Det var

alltid de bästa cyklisterna och de största stallen som hade de bästa

pacers

till sitt förfogande. Ett annat stort problem som följde med pacers var

fuskandet och alla de olyckor de förde med sig. Under nattens mörker försökte en

del dra sina cyklister med rep medan andra försökte knuffa fram dem.

7 Hours hard labour - behind the Dernys

Roy Green, Coureur Sporting Cyclist December 1960

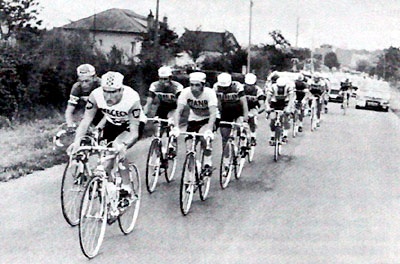

THE pace quickens from a 12 m.p.h. "club potter” to a brisk 24 m.p.h.; the pistol cracks as the 13 riders pass under the red and white " L'Equipe-Rustines " banner over the Pont de Pierre crossing the river Gironde on the outskirts of Bordeaux. The neutralised 4 km. section from race headquarters has ended, and the coureurs are on the road at the start of the 557 km. from Bordeaux, wine capital of Europe, to Paris, the French capital. The time is 2.30 a.m. on a Sunday late in May and there are far more spectators than would turn out at 2.30 p.m. for a Sunday event in Britain.

There are frequent shouts of "Allez, Bobet!" for the 35-year-old idol of the French crowds, and quite a few calls of "Bravo, Biquet!" These are the two favourites of the crowd, little Jean Robic, past Tour winner, at 39 now on the threshold of veteran's category, but unlikely to figure on the finishing list, and the doyen of the French sporting public, triple-Tour winner, Louison Bobet, strongly tipped to add this year's edition of the French "Derby of the Road" to his 1959 success.

Despite the early hour, the main square in Bordeaux was crammed with people, crowding round the team cars, in a nocturnal examination of machines. The appearance of each rider had been the signal for small boys to break through the barriers with appeals for autographs.

The machines differed very little from my own or those of my friends, in equipment or general appearance. The wheels were of normal 32-40 spoking, beautifully balanced and free-running, shod with 8-9 oz. Italian tubulars - the Bordeaux-Paris roads were comparable with the average time-trial course, apart from the odd cobbled stretch through a village.

The gears, brakes and chainsets, though naturally of the highest quality, could be bought in any “gen" lightweight shop in Britain. The frames of these supermen of the bike game were similar to the products of Mr. Lightweightman of Great Britain, with, if anything, slightly "heavier" lug designs and noticeably staunch rear triangles. Very little clearance under fork crown or rear bridge, because no 'guards are ever used on these thoroughbreds. In these days of one man - three-or-four bikes, quite a few British racing men will have frames built to these limits (and regret it after a soaking return from an evening's training in "flaming June"!).

No 24-hour man's "gimmicks" of sponge-rubber taped to the 'bars ; these were covered with normal cotton tape. The other point of contact, the most vital, showed the continued popularity of Brooks' saddles. Most of the bikes had these fitted, with the tops rather more supple than the saddles used in British time trials).

Just clear of the town now, the peloton forges into the night at a steady 23 m.p.h. Through the villages the riders are encouraged with enthusiastic applause. Many of the people are clad in pyjamas and dressing gowns. Alarm clocks had no doubt been set at an unaccustomed hour to give these keenest of supporters just a fleeting glimpse of the 13 " giants of the road." At 3 a.m. on a Sunday morning back home, I reflect, the British time-trialist will be deep in slumber, with three or four hours to go before his starting time.

The quiet of the countryside is disturbed by the noise from the many following cars in the caravan, by the exhaust cacophany of the motor cycles bearing reporters and photographers and the police escort. The tunnel of gloom ahead is pierced by the many headlights long, grotesque shadows are cast on the cottage walls through the villages a sudden vivid blaze of light from the rear of a motor-cycle means that a cine-cameraman is adding footage to his newsreel chronicle of the race, aided by powerful floodlights mounted on his camera. Ahead of us, the speed cops are waving any approaching vehicle to the side ; the police vanguard is followed by the car of the directeur de la course, lit like a Christmas tree, a flashing beacon on top giving ample warning of the race's approach.

The inky blackness of the sky is relieved to the east ; dawn is near. Looking round the caravan, I see that the rear-s'eat occupants of the press-cars are dozing ; these boys know full well that the action of Bordeaux-Paris will not really start until Chatellerault, some 250 km. from Bordeaux ; it is here that the race really comes to life. This is the place nominated this year for the " prise des entraineurs," the taking up of the Derny pacing bikes.

From the first Bordeaux-Paris, in 1891, won by the Englishman G. P. Mills when the event was open to amateurs, the "Derby" has always been paced, either wholly or in part, various types of pacing machines, both human- and motor-powered, being employed.

The pacing vehicle has been standardised since 1938, with the Derny (a moped with the small engine continually assisted by the pacer pedalling a high fixed gear), providing the shelter for the riders.

The journalists are right. Nobody is going to start an attack in the early hours of the day, with so far to go, especially with the wind blowing into the riders' faces quite strongly.

Main action of the morning, with plenty to occupy the many photographers in the caravan, comes just beyond Poitiers, at 219 k.m. The directeurs techniques of the various trade teams had decided that it was time for their riders to change from heavy jerseys and tights to normal racing attire.

Photographers rush frantically from group to group of the disrobing riders, who snatch a hurried snack and drink whilst completing toilet operations. Robic's bike receives attention from the mechanics ; the brief halt is a golden opportunity for any small fault, not otherwise worth a stop, to be remedied, any suspect wheel or tyre to be changed.

After their morning " refresher course," the riders move off in ones and twos, a bunch of about eight forming quickly and moving quite fast, the stragglers chasing furiously to make contact. We are nearing Chatellerault now, the assistant race director in whose car I am privileged to have a seat, is busy, with the cooperation of the motor-bike cops., clearing the unofficial cars from the course. During the paced section the road will be totally closed for the passage of the riders.

More press cars have joined the caravan, also several more motorbikes, photographers on the pillions. These worthies are threading their way amongst their acquaintances following the race - shaking hands, exchangling news of the race so far.

Over our car radio comes the voice of Raymond Louviot Directeur Sportif of the Rapha-Gitane concern, giving his views on the chances of his two coureurs.

Looking behind we see the French Radio car alongside the Rapha van, mike held across the gap to pick up Louviot's words and relay them to the listening millions. French radio coverage of a bicycle race is a technical marvel.

About 10 km. from Chatellerault, we pass the peloton and speed on to the town to supervise the procedure of taking up the pacers. We take the left-hand side of a wide, dual-carriageway, the side signposted for the riders, the right side being for the press and following cars. In the town the crowds are the densest seen so far. Mechanics stand with spare machines at the ready, should any rider require a change.

Further on are the entraineurs (pacemakers), with their Dernys. They are clad in racing gear ; the rules of pacing are very strict, the pacers being checked that they are not padded in any way. The machines, too, have been measured to ensure that they do not have a shorter-thannormal wheelbase, so that each rider is afforded roughly the same amount of protection. The previous day, in Bordeaux, the riders' machines had been measured from bottom bracket to front fork end to make sure that only orthodox machines were being ridden. The forks were sealed with fine wire and taped to prevent alteration.

We pull over to the side opposite the pacers to watch the proceedings. After a few minutes, the noise from the crowd at the end of the road grows louder, then 13 riders swing round the corner into view, the pacers move off, shouting and waving at their particular rider. Further down the road, the second-string pacers join the melee. The scene is temporarily one of confusion ; after a while, the riders settle down behind their own pacer, the reserves keeping out of the way, to one side.

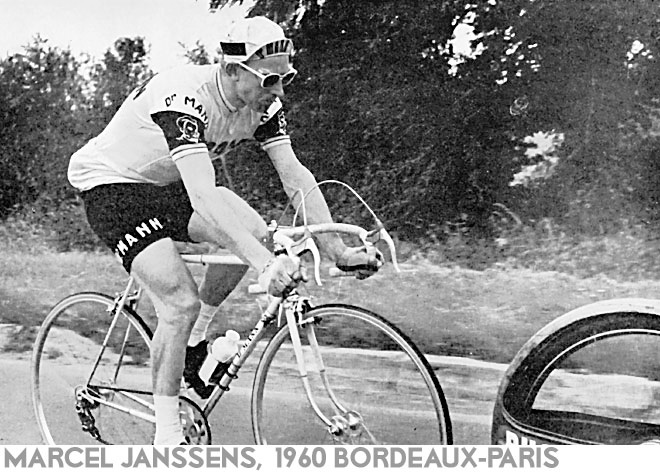

First into their stride are Bobet, Viet, Varnajo and Sauvage, opening a slight gap, but the peloton re-groups just outside the town. The first solo breakaway is the young Belgian, Marcel Janssens. Following him we notice his easy, effortless style, pedalling beautifully, at 105 r.p.m. on a fair-size gear, descending a moderately steep gradient through a village over the pave, with the car speedo showing 70 k.p.h. He rides to the right of his pacer, to combat the fresh wind coming from the front, to the left-hand side. After 35 km. alone, however, he is swallowed up by the peloton.

Louison Bobet seems ill-at-case. He has already been in trouble with the commissaires, who spotted that his velo had no wire and tape round the front forks to show that it had been passed. Bobet had to dismount quickly, let the commissaires take a quick measurement check, hop back on to the bike, then make frenzied chase after the bunch. Following him, his action seems somewhat forced, shoulders heaving from side to side climbing the gradients. But he rejoins the peloton after five or six kilometres of lone effort.

It is early yet for attacks, but the young French rider, Claude Sauvage, undeterred by the distance still to go, is the next to try. He is only allowed the lead for 10 km., however, for with 200 km. remaining, little Albert Bouvet, the French pursuit champion, takes over. What a Tryer! "Flying” downhill, riding with a “pushing” style on the flat and up hill, not losing much of his speed up the drags, well adapted for Derny pacing by virtue of his low, forward position on the bike ; here we have a picture of a man riding to his limits.

But 150 km. still remain to the Parc des Princes, and the hot afternoon sun glares down from an almost cloudless sky on the small figure punching away at the kilometres of the N.10, stretching straight as a die into the distance. A momentary easing as he snatches off his goggles, throws them by the wayside, takes a quick drink from his bidon.

Through the cobbled streets of Vendome the crowd is wild with delight at the lead of the popular Frenchman, shouts of " Bou-vet, Bou-vet ! " encourage him as he streaks round the sharp bends in the village, front wheel inches from the rear of the Derny. 'Tonin Magne, directeur sportif to Bouvet and Bobet, moves up in his van to pass over a musette in the feeding zone, keeping well to the rear of the rider as the rules demand.

Bouvet's lead on the field is now seven minutes. We wonder where the Master, Bobet, will make his attack. Our driver reckons that near the valley of the Chevreuse Bobet will pass "comme une fleche!"

But the rider who eventually quits the companionship of the peloton "like an arrow" is not the man everybody is hoping will win this race, Louison Bobet, but the first attacker of the day, Marcel Janssens. The Belgian rider is a fine all-rounder; he came nearest to giving his country her first post-war Tour win, in 1957, when he was second to Anquetil in the " Grande Boucle."

At Chateaudun, with 136 km. of the course remaining, Bouvet is leading by four and a half minutes. At Bonneval, 16 km. further on, he looks desperate as the motor-cycle messenger holds up a blackboard bearing the news - " No. 7 a 2 1/2 min." Another 26 km. and the large crowd in the town of Chartres, 94 km. from Paris, sees the lithe figure of Janssens overtake the struggling Bouvet at 35 m.p.h. Farther on we see Bouvet relegated to third place on the road as the Breton Mahe passes in pursuit of the flying Janssens. Then a little later Bouvet is passed by a group headed by one of the pre-race favourites, Cerami, the 38-year-old Belgian, who received a new lease of life this year by winning Paris-Roubaix and Fleche Wallone.

The original 13 have been chopped to nine now. Robic was the first to give best to the heat and accumulation of kilometres after about 180 km. of the paced section. The young Sauvage has paid for his early efforts and continues the journey in the sag waggon, together with Varnajo and Van Tongerloo. The legend of Bordeaux-Paris - "The race that kills " - has come true for these unfortunates. But not for the man whose name we hear continually over the radio - " Janssens, encore seal en tete ! " - Janssens, still away alone, and in command of the race.

Now we are approaching the final, vital section of Bordeaux-Paris, the dreaded long drags of the Valley of the Chevreuse. Janssens climbs out of the saddle up the ramp of St. Cyr de, Dourdan, bike swinging rhythmically from side to side, his pacer, Cools, now by his side, encouraging him - "Allen Marcel, the race is yours, Mahe is four minutes down."

But the race is not yet won, the worst of the climbing through the valley is yet to come before the run downhill to Versailles and the final kilometres through the streets of south-west Paris to the Pare des Princes. They say that every rider of this 360-mile race must suffer a defaillance somewhere along the route ; it is the man who surmounts this bad spell best who will come through the victor. But the Belgian, who has ridden strongly throughout, has no respect for reputations, neither that of the course, nor of Louison Bobet, the man behind from whom the enormous crowd lining the slopes of the hillsides, is still expecting a "miracle" come-back attack. But Louison, fighting back after a bad patch over the plain of the Beauce, is more than eight minutes down on Janssens, who is now attacking the final slopes of Chevreuse.

Now in the saddle, now dancing vigorously, the lithe figure climbs strongly to the tumultuous welcome of the crowd. The sporting French fans, - who have travelled by bus, car, scooter or bike to this noted beauty spot, although longing to see their idol, Louison, at the head of things, are applauding this young Belgian, shouting his name, clapping him all the way, swaying back to the sides of the road as the police motorcycle vanguard scythe a clear path for the rider and his entourage.

At last the hills are over, we see a gleam of victory in the Belgian's eye as he turns to look for his team van. Hooting continuously as it forges a way through the press and radio cars, the team car draws alongside Janssens, passes him a drink.

During the race, his soigneur told me afterwards, Janssens has consumed ham and cheese sandwiches, spiced bread, biscuits and sugar, as well as 10 pints of tea. He had had a pre-race meal of chicken three hours before the start.

Theugels, the directeur sportif, presses a sponge on the back of his man's neck and gives him the news that Mahe, nearest challenger, is still four minutes in arrears.

A fantastic descent into Versailles follows, the din is terrific, the shouts of the crowd combining with the roar of motor-bike, car, and Derny engines, above the whole is the continued hooting of the klaxons of practically every car and motor-cycle in the caravan, heightening the excitement. Screeching of tyres round the sharp bends as we descend into Versailles, the speedo. showing over 80 k.p.h. On one of the sharp bends I have to duck in quickly from the side window of our Peugeot, as the Radio Europe car lurches towards us, trying to pass on a too-tight corner.

Over the bone-shaking pave of Versailles now, and swinging right just before the famous Chateau, up the Picardie Hill, a few more kilometres, mostly over 50 k.p.h. now, and the rider passes over the Seine at the Pont de Sevres. The hero's welcome for Janssens through the densely-packed streets to the Parc des Princes.

The press cars cut away round to the car park at the back of the track. I jump out, push a way through the crowds around the track entrance. As I run down the tunnel leading to the track centre I hear a terrific roar from above me as the rider enters the track. By the time I am on the green sward of the track centre, Janssens is finishing his final lap to victory.

A jostling mob of photographers, reporters, officials surround the sweat-stained figure, congratulating him, trying to get photos or a few words from the victor. Suddenly there is another roar from the crowd, the crack of a pistol, and Mahe behind his pacer enters the track. Varying intervals elapse as the other finishers sprint round the cement bowl, trying for the fastest last lap. The prize of 1,000 N.F. (£80) goes to another Belgian, Cerami, completing the 437 metres in 29.3 seconds. Showing his strength at the end of the 16-hour ordeal, Janssens is second, in 30 sec.

The biggest roar of the day goes up as Louison Bobet circles the track relatively slowly, not trying for the prime. Bobet, beaten but not disgraced, in the event on which he had set his heart on winning, dismounts wearily, the fatigue and despair show in his face. But by their great reception the crowd in the stadium show that even in defeat he is still the King of the sport in their eyes.

1960 - The 59th Bordeaux-Paris - Result

1. Marcel Janssens (B), the 557km. in 15h. 59m. 55s.

2. Francois Mahe (F) - at 4m. 16s.

3. Pierre Oellibrandt (B) - at 4m. 48s.

4. Louison Bobet (F) - at 7m. 18s.

5. Pino Cerami (B) - at 9m. 20s.

6. Albert Bouvet (F) - at 13m. 26s.

7. Leopold Roseel (B) - at 13m. 29s.

8. Jan Zagers (B) - at 18m. 46s.

9. Bernard Viot (F) - at 41m. 23s.

Non-finishers: Robic, Varnajo, Sauvage, Van Tongerloo

Nedelec Sets New Record for Bordeaux-Paris

Hoban roared off after 270 miles at evens

Cycling 6-Jun-1964

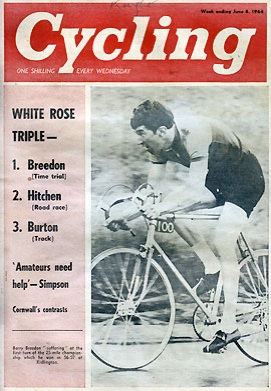

MICHEL NEDELEC, a Breton pursuiter, slim and delicate looking, proved that even a frail trackman can succeed in the hard road game when he sustained, alone, a 110-mile break in Bordeaux-Paris, to set up a new event record for the first time in 11 years.

The youngest rider in the event, at 24 just one month younger than our own Barry Hoban, Nedelec did not really believe in his own chances. Too many failures in hard events in the past had given the Breton a complex about his own success during the two years he has been a professional.

"If Michel can really gain some confidence in himself he can go a long way” Tom Simpson told CYCLING before the race, "he has lots of class, but until this year he has not really been able to master himself.

" As a trackman he was very good and got the French amateur hour record, and was a brilliant pursuiter, but was beaten by Marcel Delattre on the track, which gave him an uncertainty."

This uncertainty was dismissed on the road from Bordeaux. when the young Frenchman, encouraged by Tom's win last year - they are in the same team and plan to ride the Tour together - made a bold attack when he still had nearly a third of the distance to cover behind the Derny motors.

De Roo, Stablinski, Maliepaard and Groussard, confident that he would be beaten by the hills, let him go until he had a lead of more than nine minutes. Then it was too late.

Barry Hoban, who had started well and had been looked to as one of the main hopes of the new riders in the race, faded suddenly and disastrously when the Derny motors took over.

The pace until then had been a steady evens, but once the pacers came into the road, the speed leapt up to more than 35 mph, and the sudden change proved too much for the Yorkshireman unaccustomed to such a move.

He was not alone, and with Velly, Daems, Kherkhove and Maliepaard, he abandoned, simply beaten by the pace, and facing realistically that there was nothing left to be gained by struggling along at the back.

Nedelec's final victory came on four fronts at once. First, he won the race at his first attempt; second, he was never seen by the rest of the field once he had broken away; third, he broke Kubler’s record, set up when the former world champion won the event after an epic chase wiyj Wim Van Est: and fourth, Michel had enough left to win the prize for the fastest lap of the Parc des Princes track at the end. He covered the last lap in 28.6 seconds, beating his nearest challenger, the Belgian Nys, who was third, by two and a half seconds.

Jean Stablinski, the French former world champion, attacked hard towards the end of the event, when he realized the tactical error his team had made, and managed to gain two minutes on Nedelec, though he still came in more than seven and a half minutes down the new youngster. But during this period Michel had continued to gain steadily on the pursuing field in any case. proving that it was a battle of one strong man against another.

This was only Nedelec's second big win with the professionals, both of them gained on the same day. Last year he won the Tour of the Oise on the day that Tom Simp won Bordeaux-Paris.

On Sunday. his jump was severe, coming just after an attack the little Emile Daems who rides the same team, that he gained two clear minutes lead in the distance of six miles, which themselves were covered in only nine minutes.

Once this first attack had succeeded, the tall (6ft. 3in.) Frenchman simply continued as if he had all time in the world, riding steadily and without any sign of distress through the whole valley of Chevreuse, usually the testing point on the course.

RESULT

Michel Nedelec, Peugeot B.P., the 346 miles in 14-28-46, 1; Stablinski (F), 14-36-25, 2; Nys (B) 14-40-29, 3.

A New Way to Paris from Bordeaux

J. B. Wadley International Cycle Sport November 1970

“THE Big Bordeaux Battle - Full Details" said the placard outside the newsagents on the bus route from the airport to the centre of Bordeaux. But when I later bought a copy of Sud Quest I found that this was not the war I had come to report. Indeed in the Alles Tourny I met a press colleague from Brittany who figs been a regular on the Tour de France for some years, and assumed he was there to cover Bordeaux-Paris.

"No such luck" he said "I'm here for the Bordeaux by-election. It doesn't take place for another fortnight, but the place is full of journalists. You probably know that the Prime Minister of France, M. Chablan-Delmas is also the mayor of Bordeaux and has held the parliamentary seat for the last 23 years. There are eight other candidates, but the chief opposition is from M. Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber whom all the papers are calling J.J. - S.S."

Bordeaux-Paris, I found, was not front-page news. True it had the "eight- column" treatment in the sports pages of Sud-Quest but the columns were not very deep and most of the remaining space was occupied by reports of the European swimming championships at Barcelona and a preview of that same Saturday night's France-Czechoslovakia football match at Nice. In these events, at least, there was some chance of a French victory, which was more than could be said from a glance at the 16 runners in the 69th Bordeaux-Paris, known as the Derby of the Road.

This was the line-up.

1 PERIN Miche lFagor-Mercier France

2 PROUST Daniel Fagor-Mercier France

3 BEUGELS Eddy Mars-Flandria Holland

4 BODART Emile Mars-Flandria Belgium

5 MORTENSEN Leif Bic Denmark

6 ROSTERS Roger Bic Belgium

7 BRACKE Ferdinand Peugeot-B.P. Belgium

8 DELISLE Raymond Peugeot-B.P. France

9 ROUXEL Charles Peugeot-B.P. France

10 AIMAR Lucien Sonolor-Lejeune France

11 GUYOT Bernard Sonolor-Lejeune France

12 HOBAN Barry Sonolor-Lejeune England

13 FREY Mogens Fornatic-De Gribaldy Denmark

14 DEN HARTOG Arie Caballero-Laurens Holland

15 POPPE Andre Mann-Grundig Belgium

16 VAN SPRINGEL Herman Mann-Grundig Belgium

In 1968 when Bodart scored his surprise win, I followed the race from Chatellerault where the riders made contact with their Derny pace-makers after 160 miles company riding from Bordeaux. Last year I simply went to the finish at Rungis to the south of Paris where Walter Godefroot won easily. On both occasions my report stressed the diminishing importance of Bordeaux-Paris which once really was a Derby in the sense that it attracted a field of top riders who had spent weeks and even months getting in shape for the 370 miles race. Nowadays it had become a consolation event for riders who for various reasons, had had a poor season.

Why, then, had I bothered not only to cover the race again, but to travel to Bordeaux to see it from start to finish ?

There are two answers to the question. The fuel is found in the list of riders engaged. True there were several who hadn't won anything during the season simply because they weren't good enough. But there were also those, like Barry Hoban and Herman Van Springel, who crashed during the Tour de France and were forced to retire when running into their best form.

Then there were three riders who had ridden very well as new professionals and were not riding this Bordeaux-Paris in desperation but with the aspiration perhaps not of winning this time - though obviously they would try - but of gaining experience for future campaigns. In this latter category were Leif Mortensen and Charles Rouxel (second and fifth at Leicester) and Mogens Frey who in July became the first Dane to win a Tour de France stage (Incidentally if he or Mortensen had won this Bordeaux-Paris it would not have been the first Danish success Ch. Mayer won in 1895).

The second reason I had come to Bordeaux was because an entirely new course was being used. Instead of some 300 miles along the wide, straight flat N.10 there was a roughly parallel route over secondary roads which was reported to be much hillier.

This change had not been made voluntarily by the organisers, l'Equipe and Parisien Libere. They had been told bluntly by the appropriate authority that if they wanted to hold Bordeaux-Paris this year, another course would have to be found. (I was not surprised to hear this; as we approached Paris in 1968 there were serious traffic problems).

The fact that the new distance was increased by 20 miles over last year's to bring the journey up to a record 382 was only half due to the changed route. An extra 10 miles was added through the 1970 finish being on the Municipals track in eastern Paris.

There were a few well laden team cars parked in and around the Alles Tourny in Bordeaux when I arrived on that Saturday afternoon 5th September. There was a meeting of the Directeurs Sportifs at 3 o'clock in the Maison des Vins, administrative and propaganda headquarters of the Bordeaux wine industry. I had a chat with Jean Stablinski, the French ex-world champion who now directs the Sonolor team. He told me I would just catch Barry Hoban at the nearby Continental hotel before he went out for a potter on the bike.

"How's Barry going ?" I asked.

"He's riding well enough - but not very quickly!"

I did not take too much notice of that remark. Stablinski as a rider was one of the most cunning in the business. As a Directeur Sportif he is no

less astute. Some rival ears were in our little group, and that reply to my question might really have been directed at them.

Barry's bike was outside the Continental hotel, so I waited in the lounge, which I seemed to recognise. Had I been here before ? Yes, I remembered. I was here on the eve of Bordeaux-Paris five years ago. Indeed Jean Bobet (in whose Radio-Luxembourg car I was to follow the race) had booked me a room in which to get a few hours sleep before the 2-30 a.m. start. So had several others, but nobody was anxious to go to bed. This was the famous night when, after winning the 8-day Criterium du Dauphind Libdrii, Jacques Anquetil took a special plane from Grenoble to Bordeaux with the intention of riding Bordeaux-Paris a few hours later. He arrived in the Continental restaurant where we were waiting in good spirits - and hungry. Three hours later he started Bordeaux-Paris which he won with Stablinski second and battling Tom Simpson third.

Before long Barry emerged from the lift, yawning.

"I've done nothing but sleep since I came here yesterday" he said -They say that Bordeaux-Paris is won in bed - in that case I'm in with a chancel"

"How is the form?"

"I just don't know. After the accident in the Tour on July 2nd I could not ride the bike for three weeks because of the three broken ribs. When I did start again it was tough going. My back aches terribly even in training, so you can guess what it was like in races over the pav6. Gradually the pain disappeared, but the form didn't come. With the idea of riding Bordeaux-Paris I have been riding an extra 60 kms home to Ghent after races in Belgium which built up my resistance, but I had no punch.

"Then the other day in a Kermesse I managed to get across 200 or 300 metres between the bunch and the breakaways. That was something like the real Hoban. Perhaps the form has arrived at last. But Bordeaux-Paris isn't an ordinary race. I like riding behind Derny pace, but I wasn't brilliant last Sunday in the Roue d'Or at the Municipaletrack."

Barry wheeled his bike round to the garage where mechanic Lucien was busy. Another Lucien (Aimar) was adjusting his saddle; Bernard Guyot was lounging on a pile of tyres looking pensive. I could guess his thoughts - those of one who had been a brilliant amateur but whose professional career had been disasterous. If he failed to make a show in this Bordeaux-Paris he might be without a marque next year ... Soon the three Sonolor riders set out for a potter together before returning to the hotel for more sleep and a 10 p.m. meal.

The "real start" was at 1 .a.m. at the traditional rendezvous Quartre Pavillons three miles north-east of Bordeaux. But first there were the hour or so of preliminaries in and outside the cafe Richlieu in the centre of the city.

It was a nice warm night, but all the riders were well wrapped up in a variety of woollies - all that is except Mogens Frey, bare of arms and legs. The TV lights and cameras were busy, radio-reporters too. I heard Barry Hoban correcting one "speaker" who had described him as a newcomer to Bordeaux-Paris "I started in 1964, my first year as a professional, but retired at Chartres." Among the fair-sized crowd I found Archer Road Club's Terry Ewing who has been riding well with a Bordeaux club and won five races; Terry was with the Northern Ireland rider David Walker an experienced rider in French events. I lick the pair and an English friend to have a chat with one of the Bordeaux-Paris field who had belonged to an English club - and I don't mean Barry Hoban.

"Yes" said Eddie Beugels of Holland, I belonged to the Kentish Wheelers for six months. I was over to learn English. I used to go up on the Southern Railway from Sittingbourne to Cannon Street every day with the city gents. I used to read the "Times" but did not get around to wearing a bowler hat. I worked in a laboratory. I enjoyed my time cycling with the K.W's. I even won a hill climb at Sundridge - it was steeper than anything we've got in Holland."

At half-past mid-night after much blowing of whistles and appeals to Messieurs les Coureurs Albert Bouvet led the procession of 16 over the Pont de Pierre for the neutralised ride to Quatre Pavillons, accompanied by hordes of bikes and mopeds. A ten minutes stop on the famous crossroads, then at 1 a.m. precisely they were off on the "new route" (in fact the first 120 kms was the same as that used in pre-war days before the construction of the bridge over the Dordogne opened up a shorter route to Angouldme).

Sixteen men on a 150 miles all-night ride and no need to look for signposts. About 100 yards ahead was a horizontal strip of six green lights the width of a gendarmerie car whose driver was matching the movements of two motor-cycling colleagues ahead following the plentiful Rustines direction arrows. (Rustines, puncture outfit and vulcanising kit makers, were again main sponsors of the race).

The odd man out of the 16 was the "stripped" Mogens Frey who soon found the night not to be as warm as he had imagined, with patches of mist gathering in the undulating road to Libourne. The Dane was soon making signs to his team car, third in the line of technical vehicles on the right of the road. We were in the leading cars in the left file. The Dane dropped behind us, to reappear a minute later snugly dressed like his companions with arm and leg warmers and a woolly hat.

Viewed from behind in a comfortable car the pack made a pleasant sight in the flood of light from our headlamps, the back plates of their pedals blinking back at us as they twiddled little gears to keep legs warm and supple.

They were out of the saddle on the slightest rise, for the idea behind a lot of "dancing uphill" is not to overcome the stiffness of the gradient but to prevent numbness and seat-soreness through constant saddle pressure. As on any clubrun there was a bit of larking around, Bracke and Bodart (two friends and neighbours from the Walloon area of Belgium) dropping off 20 yards then sprinting back for some imaginary prime. There were several other pairings during the night of riders from rival teams drawn together through language or friendship. Two pairs of new professionals, for instance: the two Danes, Mogens Frey and Mortensen, the two French boys Rouxel and Proust who had ridden so often together in amateur competition. They chatted together, they ate together (banana skins were frequently tossed into adjacent vineyards) and perhaps most companionable of all, they stopped together to satisfy personal needs.

The pedalling rate on the small gears and occasional stretches at 25 m.p.h. created the impression that the field were gaining on their 211 m.p.h. schedule. In fact they were down on it a lot. The explanation was that the mist was becoming very thick in patches. Until drivers realised they were now a nuisance rather than a help, the peloton had a ghostly look in the diffused light of the following cars' headlamps.

A feature of Bordeaux-Paris on the old route had been the night-long interest of the public. On my first contact with the race, in 1956, we talked with an old chap outside his roadside cottage and found he first saw the Derby in 1899 and had not missed one since. There certainly would have been scores of others with a similar attendance record, perhaps even a super-veteran who, as a child, saw the very first version in 1891.

How would the public react along the new course ? At first I thought the interest only slight, but soon every village was thronged with spectators. I noticed one poster for a Bordeaux-Paris ball: possibly there were others along the route arranged for dancing to go on far into the night until the imminent arrival of the race. And in one small town the riders were cheered on by a wedding party, complete with bride and groom who must surely have been as much in love with cycling as with each other. It was then half-past three a.m....

In the country too, they were waiting in smaller groups outside their homes often in dressing gowns or a variety of sleeping attire.

Was it worth staying up late before going to bed, or getting out of it in the small hours to watch 16 cyclists and a score of cars and motorbikes pass by in a couple of minutes? The answer will not really be known until next year if the race goes that way again.

Just after seeing the wedding party we became aware that although the 16 riders seemed to be on a club-run, they were under no obligation to remain on friendly terms. Vaguely and sleepily we had noticed Eddie Beugels drop from the bunch and behind us, presumably for a brief roadside stop. In due course back he came very fast, went right by the bunch and was away on the first cousin of an attack with 100 miles still to be covered before making contact with the Dernys at Poitiers.

Maybe it was because he was getting cold or just bored. Or perhaps it was a serious attempt to make rival teams work a bit harder while his own team-mate Bodart (who, remember, won in 1968) had an easy ride. At any rate little Bernard Guyot went after him, sat on his wheel for a few minutes, until with only a slight accelleration from the bunch, the pair were caught.

Despite this and one or two other similar skirmishes the five hours of darkness had put the race an hour behind the 211 m.p.h. schedule. It was well beyond Ruffec (starting point of the 21st stage of the 1970 Tour) before car lights were extinguished. Now the roadside spectators included lone hunters and shooting parties with their eager dogs, priests and communicants gathered on church steps, rugged peasants about to begin a long Sunday's overtime in the fields.

It was the beginning of another day for the riders, too. Just as he had been the last to put on warm clothing for the night, so was Mogens Frey the first to begin stripping off, the arm warmers for a start, then the leg. For the third time in two hours Van Springel made a certain sign back to his car, and by now he and his helpers had the Operation Penny drill off to perfection. Not a bidon, not a banana, not a spanner, just a ration of toilet paper. V.S. grabbed it, rode for a few hundred metres until he found a convenient spot to execute his urgent business.

We were now approaching Poitiers where the Derny pacers were waiting. In the seven previous Bordeaux-Paris events I had followed the "Derny town" had been Chatellerault and on each occasion I was there about half an hour before the take-over to enjoy the fun. The atmosphere was really something special, the tension building up as the riders grew nearer, the pacers literally running round in circles as they pushed Dernys into smoky, spluttering life. Then came the riders sprinting through the double row of spectators, but before settling down to serious work there was the

inevitable Bonjour shakehand between pacer and follower.

In the past it was possible for us to see all this in comfort and then follow on a few minutes later in the press cars knowing full well that for the next 100 miles the NA 0 was as wide as a motor-way with a load of room for us all. But in this 1970 Bordeaux-Paris the prise d'entraineurs was immediately followed by a -D- road which promised to provide traffic problems for a time at least. Accordingly our driver judged it better to move ahead just before Poitiers and for us to look back at what was going on. A wise decision. although the actual take-over point was on a wide by-pass road, we were soon on the narrow D3 looking back at 16 Dernymen, their followers, eight team cars, a personal van for each of the 16 riders, 16 reserve pacemakers, eight or nine official vehicles, half a dozen motor-bikes and passengers and a dozen press cars whose passengers apparently preferred such congestion rather than enjoy the freedom of the road ahead.

Often there is an immediate attack when the Derny-paced session starts, but today it was calm. Perhaps the riders were anxious about the extra 20 miles and were being cautious. Whatever the reason the effect was that they kept together riding at about 27 m.p.h. as compactly as they had on the 150 miles 18' m.p.h. clubrun from Bordeaux to Poitier.

At La Roche-Posay a banner across the road announced a RavItaillement - ter Service. In fact it was the third sitting of the Bordeaux-Paris feeds. The first two had been in the eight mile zones during which the riders were free to take on food and drink from their following cars. Now with the Dernys all together and on narrow roads, the feeding had to be done in relays, each team car moving up in turn with supplies of food and drink.

First to be served with their mobile late breakfast or early lunches (it was then 10-15) were Hoban, Aimar and Guyot of the Sonolor-Lejeune team.

Immediately the 13 miles feeding zone was over, Leif Mortensen attacked on a long hill - and the race had really started roughly mid-way between Bordeaux and Paris. He was chased by Van Springel and the speed shot up to nearly 40 m.p.h. when the plateau was reached. The 14 others were strung out in a long line the first to be dropped being Mogens Frey. an

ironical situation since the man responsible was his compatriot Mortensen.

It was significant, this reaction of Van Springel to the Mortensen attack. In 1967 V.S. had ridden Bordeaux-Paris and did not take an early attack by Van Coningsloo seriously. By the time he did, it was too late with the final result. 1 Van Con; 2 Van Spring. This time he did not mean to be taken by surprise.

Significant, too, was the fact that Mortensen's team car was soon up behind him with a radio appeal coming over for the reserve Bic vehicle to move up to take its place behind the ' peloton." After a spirited chase Van Springel caught the Dane, and not liking the look of each other the pair eased and were soon caught. The pace continued fast (30 m.p.h.) but regular through pleasant wooded country, with fields of ripening fruit, maize and grapes prominent in the more open spaces.

With the field compact the "second sitting" of food and drink was again performed in relays, during which time one or two reserve Derny pacers came up to relieve their No. 1 men who dropped back to a van to snatch a bite and a sip and also a can of oil for their thirsty engines.

The second feed over, the second movement began. In 10 kms young Proust had built up a lead of two minutes and the bunch could not have cared less. The Fagor boy had been one of the chief sufferers during the Mortensen-Van Springel raid, hardly able to maintain contact. His "attack" was clearly a suicide bid designed in some small way to help team-mate Perin who was third last year. Sure enough a slight quickening of the pace behind was enough to pull Proust back not only to the "peloton" but off it almost immediately, in company with the distressed Bernard Guyot and Ferdinand Bracke. What a tragedy for both these riders. The Guyot case I have already explained. As for Bracke, he had elected not to defend his world pursuit title at Leicester in order to train seriously for Bordeaux-Paris - and there he was a casualty with hardly a shot yet fired in anger.Even so there was already a stretcher case in Mogens Frey who fell after his pace-maker had touched another (Frey 's No. was 13 ...).

Meanwhile Barry Hoban had been sitting nicely behind his Derny and getting maximum shelter - the wind was negligible. Approaching Blois we thought of the tragedy in that town 11 months earlier when a distinguished pace-maker Ferdinand Wambst, who had starred in so many Bordeaux-Paris races, was killed in a track crash in which his follower Eddy Merckx was badly injured.

Enormous crowds cheered the field through Blois at the beginning of a beautiful 35 miles stretch on the southern bank of the Loire commanding views of stately castles. We jotted down other information tounstique in oyr notebooks. Rich soil, pretty cottages, flowers, plum and apples orchards, a couple of G. B. motorists wondering why they were being pushed on to the verge by motor-cycling police ...

There the recording of trivialities stopped. A new line of the note book for something important. in capital letters and a star:

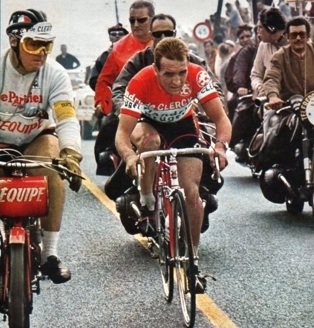

*HOBAN ATTACKS!*

When Barry had a minute we were able to drop in behind. On our right was Race Directeur Jacques Goddet. "This is as it should be" he called out to me "An Englishman leading the Englishman's race!"

An Englishman G. P. Mills had won the first Bordeaux-Paris in 1891; in 1896 a Welshman Arthur Linton was joint first with Gaston Rivierre; in 1967 Tom Simpson took the Derby. Was Barry Hoban now on the road to emulating his late rival and friend ?

Barry looked strong and comfortable, hands on the tops, his front wheel only an inch off the Derny mud-guard. At Clery Saint Andre, with 103 miles still to go the lead was 2m 10s. Then I was startled to notice that there was no Sonolor team car behind our man. This meant, perhaps, that Stablinski had no confidence in Hoban and preferred to keep an eye on Aimar who was riding well. At length a van marked "Hoban" drew up behind its man, but over the short-wave radio we got news of the approach of a less friendly Van, Van Springel,and sure enough on the approach to Orleans he came up to and past the Englishman with a rush pursued by the tenacious Aimar. A sympathetic press colleague called from his car:

"Orleans never was a good place for an Englishman to be in!"

We could not have been many metres away from the scene of Joan of Arc's victory over les Anglats in 1429.

But Barry was not yet beaten Caught by Rouxel and Mortensen, he managed to renew company with Van Springel-Aimar, but almost immediately the Dane was dropped and was overtaken by his team-mate Rosiers. At length Barry lost contact, too. as Van Springel-Aimar began another passage of arms which soon put them out in front ahead of the second -tandern- Rouxel-Rosiers. For 20 miles the "accordian" was played. with Van Springel clearly the strongest and Hoban the weakest.

Here I must mention that on my first Bordeaux-Parts in 1956 I was impressed by the thorough way the clothing of the pacemakers was checked to see that no unfair advantage was gained by increasing the area of shelter. For this 1970 race the rules were the same; the stipulated clothing being;

One under-jersey

One racing jersey with long sleeves. If this has back pockets they must be sown up so as to be unusable.

One pair of racing shorts of the same type used by the bicycle riders.

One pair of cycling shoes.

One pair of black or white socks.

One pair of gloves, racing or ordinary, without sleeves. Muffs are forbidde.t.

One racing type of crash hat.

All this kit should be of the same size normally worn by the pacemaker.

I particularly checked these facts on noticing that one or two pacemakers had added some kind of plastic under-garment several inches of which was showing below the over-jersey. This obviously increased the bulk a little. It also has a fascination for one or two riders who could not resist the temptation of grabbing it. These brief sessions of fraud must have been invisible to the Commissaires who also appeared not to notice that one or two pacemakers seemed to have ballooned out a lot since Poitiers. One such was Aimar's ...

Aimar's Directeur-Sportif it will be remembered, is Jean Stablinski. The man in charge of Van Springel was Frans Cools a man no less astute, today he was not watching proceedings from a following car but was actually pacing his man. We learned afterwards that he realised Aimar was 'less at ease" behind his No. 2 pacemaker than behind the "Big One". Accordingly Cools made a premature stop to fill up with petrol from the following van, and was already back pacing Van Springel when Aimar's No 1 stopped for the same purpose.

And so "less at ease" behind the reserve pacemaker, Aimar was unable to reply to the violent attack which the intelligent Cools launched at the critical moment. It certainly was Cools' attack rather than that of Van Springel who shouted out for him to ease the pace. Had it been an ordinary pacemaker in front Van Springel would no doubt have been obeyed. But as this was his Directeur Sportif there was no arguing. They got rid of Hoban and Rouxel and above all of Aimar. Only Rosters remained, and he only lasted nine kilometres.

We dropped back behind Aimar and watched his furious chase to rejoin Rosters; the pair were now condemned to fighting for second place. Then we joined the motorized armada behind Van Springel, barring accidents, the certain winner of Bordeaux-Paris.