Cycling Caps

Why I Never Ride Without a Cycling Cap

This hopelessly traditional, possibly outmoded, remarkably humble piece of headgear screams panache. (And it's really practical.)

BY TOM SOUTHAM

(Photo by Colin McSherry)

I put on a cycling cap every day that I ride my bike. I've done so pretty much since I became a professional cyclist, when I felt that I had finally earned the right. Lately though, I sometimes feel ridiculous. Now that I am retired, why do I still feel the compulsion to stick so resolutely to this tradition, looking in the mirror each morning, straightening my peak before I head out the door?

Many of us have a bit of a 'first girlfriend' syndrome with cycling, an intensity and excitement that springs from the image of the sport the way it was when we first found it. For me, the cycling cap is central in that image. I haven't moved on from a scorching July day in France in 1990 where I watched a yellow-jersey-clad Greg LeMond help his Team Z teammate Ronan Pensec to victory in a post-Tour criterium. It was an important milestone for me: Not only was it the first professional bike race I saw in person, but it was also the day I bought my first cycling cap—and began an almost lifelong association between those distinct little cotton caps and the sport I love.

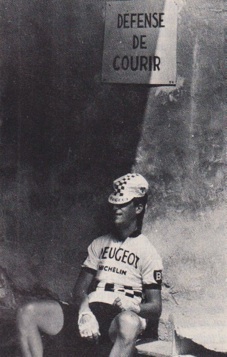

IN THE EARLY days of pro racing, the cycling cap was purely functional. Riders wore plain, white skullcaps that eventually turned shades of brown and grey with dust from the rough roads of austerity on which cycling grew up. There was something a little ironic about the cycling cap then. The riders of the day were tough men—more like coal miners and boxers than the svelte thoroughbreds of recent years—and the cap was a dainty thing. In pictures it looks as if riders thrust the caps onto their heads in disgust, as though forced to by their mothers, to avoid catching a chill.

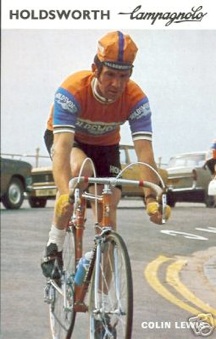

Up until the sixties I can plot the cycling cap's history only by studying the kind of black-and-white images that have become so iconic you wonder if reality at the time was in color at all. I found a little color through the eyes of Colin Lewis, a member of the 1967 British Tour de France team. Lewis is renowned for his love of cycling caps—his teammates, he tells me, used to joke that he "had a six-inch nail in his forehead to hang the thing on."

When Lewis began racing in the early sixties, cycling caps were popular among riders, but they weren't easy to come by. "Times were harder then and racing caps cost money, so not everyone would have them," Lewis said. "No one had helmets, and a cap was very practical; firstly it would keep the sun out of our eyes, secondly it absorbed the sweat, and thirdly it kept the rain and muck out." "When I turned pro, along with our salary we got 24 cans of Mackeson's Stout and six racing caps a month," he continued. "But we still got them infrequently because the guy in charge of distributing them was selling them on the side!"

For Lewis, the cycling cap was a badge of honor, a mark of professionalism, and not something a rider would want to give away. "When I got selected for the Tour de France, my team gave me something like 10 cotton racing hats. I was very fond of a good starched racing cap, and I was proud of having a nice fresh one on each day," he said. "But on day three, Tom Simpson came alongside me during a bit of a lull on this long stage and said, 'Gi's your hat.' I said, 'Sorry?' He said, 'Give us your hat!' I said, 'Well, what for?' And he said, 'I want to have a shit and I need to wipe my arse on something!' I had to ride bloody 200k with a bare head, then."

The cycling cap may have been a very functional piece of kit, but its real evolution began when it became viable to do exactly what Lewis had been so reluctant to embrace: give it away. In the seventies, as the cost of producing caps came down and sports marketing evolved, the cycling cap became the ultimate souvenir—a link between a generation of cycling fans and their heroes. For a sponsor, the idea of someone wearing your brand on his head was no doubt worth the production cost of any number of thousands of hats per year.

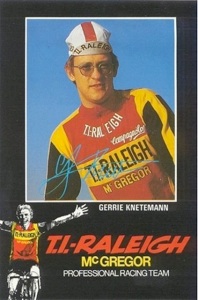

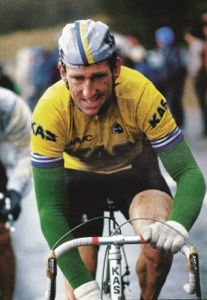

OVER THE NEXT two decades, the cap enjoyed a high water mark: TI-Raleigh riders storming the Alps with their caps pushed up high on their heads; Sean Kelly hitting the cobbles with his cap turned backward like a man ready to dive into a fight; Giuseppe Saronni, impeccable with his peak flipped up at the front, signing autographs in his Colnago-branded rainbow jersey.

Wearing the cycling cap became an art in itself. The greats all had their own styles, and the rest of us gleefully imitated them. The cap stood proud on the heads of professional cyclists not only in races, but also in their team postcards, on podiums, as well as on the heads of managers, mechanics, and fans alike; the whole cycling family had chosen the cap as its dress code. The cap also became an attainable sign of allegiance for fans. "When I was growing up in Idaho in the 1980s," says Luke Batten, co-creator of the popular Tenspeed Hero blog, "we just wanted to be a part of the culture any chance we had. We could not afford a Campagnolo-equipped bike, but we could afford a Campagnolo cap." This was also when caps started showing up in pop culture—most famously on Spike Lee in She's Gotta Have It and later perched on Wesley Snipes in White Men Can't Jump.

It was around the nineties, though, that things started to change for us pros. In 1991, UCI rules stated that helmets were optional for professionals but compulsory for amateurs. The immediate effect was that to any aspiring young amateur forced to wear a helmet, the cycling cap became the mark of a true professional. The rule stood until 2003, when helmets became mandatory for everyone.

Perhaps it is quite telling that the entire period in which I longed to be a professional spanned almost exactly these years. (After going to my first race in 1990, I would turn pro in 2003 with Amore e Vita.) By then, I knew in my heart the cycling cap's days in racing were numbered. And I had managed to race just once in a cap as a trainee the previous autumn. In time, most riders chose to train in helmets, too. The two weren't mutually exclusive, but the number of occasions when we wanted to stuff a cap under a lid was limited to the very cold and the very wet. Suddenly the cycling cap seemed to have no place. The cap got outmaneuvered off the bike too, usurped by the more uniformly accepted baseball hat. Cycling caps, with their various crooks and peaks and funny angles, had potential to go wrong on the podium. Baseball hats not only did the job, they were also an obvious choice for a younger generation of bike riders influenced more by popular culture than by cycling tradition. And by 2010 the cycling cap no longer seemed to have a practical purpose. A few riders would pull crumpled ones out of their pockets and don them at the cafe, and some would wear them to the start of races and give them away to spectators. The cap that had once protected necks from sunshine, eyes from rain, and unified the cycling world and those who wished to be a part of it was almost nowhere to be seen.

The idea that the cycling cap might one day die off seems a bit far-fetched, but it takes only one generation for things to change. Mine might never forget it, because the cap is so central to the way cycling was when we first fell in love with it. But what about the young kids discovering cycling today, whose heads will be filled with images of riders who roll up to the start line with impressive haircuts and then climb onto the podium in a baseball hat?

FORTUNATELY, THE CAP is experiencing something of a renaissance that might yet be its saving grace. While no one was really watching, cycling caps stopped being the uniform of just the dedicated cyclist, and became instead an identity patch for all sorts of people. Tenspeed Hero and many other specialty makers now design caps that are bought and worn all over the world by everyone from cycling enthusiasts to fashion-conscious creative types. Amazingly, perhaps because of this hip rebirth, the cycling cap has found its way into the peloton again. Mark Cavendish consistently appears at the start of races with a cap placed jauntily on his head. One might be tempted to think that the British sprinter is being flippant, but Cavendish is a rider who acknowledges the traditions and history of cycling. It is conjecture of course, but I feel his adoption of the cap is a way to show that he understands the rich heritage of the sport that he is now, and will forever be, a part of.

Had the cycling cap existed solely for function, it would have gone the way of toe clips, plus fours, and goggles. Thankfully it has proved that it is more than that. No other sport uses similar headwear, which makes it uniquely ours. And that is its true essence: It is more than a functional or promotional item. Just like a policeman's hat or a soldier's ceremonial headgear, the cycling cap has come to mean something much greater than the sum of its four cotton panels and tiny brim.

The cap might be an old institution, its real function all but gone, but people are wearing them again. I cannot truthfully be sure of their reasons. In the cold light of day I tell myself I wear mine because I am a fan of the sport. I have a BigMat cap that belonged to a dear French friend with whom I raced many years ago and whose company the geography of our diverging lives forces me to miss. I have caps from teams I myself have ridden for. I have caps from small brands trying to get started and others that bear the logos of some of the most famous brands in cycling. And although I no longer wear it, I have that Team Z cap that I bought all that time ago.

But really, I wear mine because I am a little stuck in time. I am stuck in a time when cycling caps were what professionals wore, and I wanted to be one, and maybe somewhere in the recesses of my brain I long to look at the sport through eyes that I'll never have again.

Tom Southam